E-voting has the potential to work, but...

Let's contribute to the IEC efforts to strengthen our democracy

In a week, when the City of Cape Town once again showcased its efficiency and grandeur, rolling out the red carpet for Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana to finally deliver his much-anticipated budget, another significant yet lower-profile event was quietly unfolding.

On Monday, the Electoral Commission of SA (IEC) commenced a pivotal conference — one that, while lacking the high-profile fanfare of the budget speech, carried profound implications for the future of South Africa’s democratic processes.

This conference, which brought together electoral experts, policymakers, and stakeholders, delved into critical discussions about the potential implementation of electronic voting.

The gathering sought to explore how digital innovations could enhance electoral integrity, accessibility and efficiency.

As the nation dissected the fiscal roadmap laid out by the finance minister, the IEC’s deliberations on modernising the electoral system signalled an equally consequential conversation — one that could redefine how South Africans engage with their democracy in the years to come.

While South Africa has never shied away from embracing bold ideas and introducing progressive policies, the true challenge lies in their implementation — let alone enforcement.

The country’s governance landscape is often marked by well-intentioned reforms that stall in bureaucratic inertia, political hesitancy, capacity constraints, ineptitude, or corruption and greed.

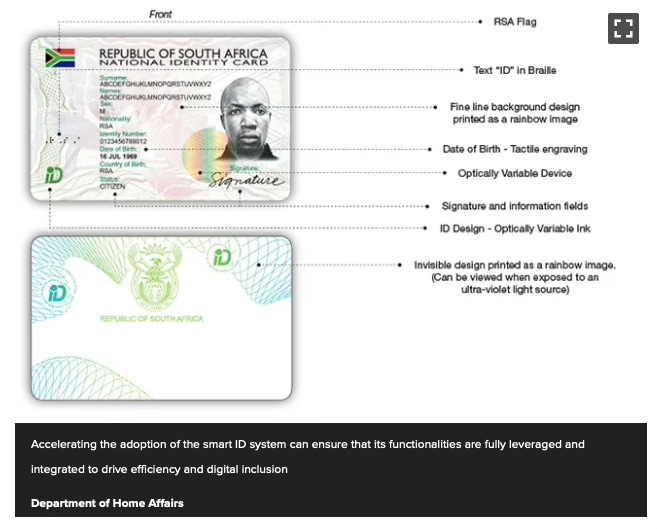

A striking example of this is the national smart identity card, designed to replace the outdated green bar-coded identity document.

First conceptualised in the late 1990s, the smart ID card was only officially launched in 2013, highlighting the government’s sluggish approach to rolling out critical digital transformation initiatives.

Built on biometric identification, this digital ID system is far from novel; Malaysia pioneered its implementation in the early 2000s, and the writer had the privilege of participating in a study tour to observe that country’s early adoption of this then cutting-edge technology.

The chip-based smart ID card presents vast potential beyond basic identity verification.

It has the capacity to integrate multiple personal credentials, serving as a secure platform for an individual’s driver’s licence, firearm licence, and health records.

Furthermore, in a truly digitised ecosystem, it could function as a seamless payment tool for public services —including intermodal transport systems such as minibus taxis, Gautrain, tolls, and other public services. This will eliminate the risks associated with cash transactions.

However, despite its promise, the full potential of our smart ID card remains unrealised, largely due to slow policy execution, fragmented intergovernmental coordination, and a lack of sustained investment in supporting infrastructure.

If the government is serious about e-government and modernising service delivery, it must not only accelerate the adoption of the smart ID system but also ensure that its functionalities are fully leveraged and integrated to drive efficiency and digital inclusion.

Elections in South Africa do not operate in isolation; they rely heavily on the integrity and efficiency of key institutions within the broader governance ecosystem — chief among them, the department of home affairs.

As custodians of the national population register and the issuing authority for identity documents, the department plays a crucial role in ensuring that only eligible citizens participate in the electoral process.

A fundamental weakness in the system is its susceptibility to exploitation by corrupt officials and cybercriminals, both of whom pose a serious threat to national security and democratic processes.

One of the most pressing concerns is the government’s failure to establish a comprehensive, integrated identity management framework — commonly referred to as a "single view" of all individuals residing in the country.

The lack of a unified system makes it significantly harder to detect and prevent identity fraud, which in turn creates loopholes that can be exploited to undermine the integrity of elections.

Fraudulently obtained identity documents pose a direct threat to the credibility of the electoral system.

If individuals who are not legally entitled to vote manage to do so using falsified documents, it not only skews election outcomes but also erodes public confidence in the legitimacy of democratic institutions.

In a political climate already fraught with allegations of electoral fraud and manipulation, the potential for such abuses could further inflame distrust and instability.

To safeguard the integrity of elections, urgent reforms are needed within the department of home affairs to enhance the security and reliability of the national population register.

This includes the full deployment of the smartcard system introduced a decade ago.

Without full implementation, our electoral process will remain vulnerable to manipulation, ultimately undermining the democratic principles upon which the nation was founded.

Perhaps the most glaring issue in the e-voting debate — the proverbial elephant in the room — was conspicuously absent from discussions throughout the conference’s three-day duration: South Africa’s reliance on foreign, particularly US-based, technology vendors.

The risks of such dependence are far from hypothetical.

US President Donald Trump’s administration, under the heavy influence of venal tech oligarch Elon Musk and other corporate interests, demonstrated how economic power could be weaponised to advance foreign policy.

This policy not only prioritises US strategic and economic dominance but also actively serves the business interests of Trump’s billionaire allies, often at the expense of global partners.

This reality raises serious concerns about entrusting key elements of our electoral infrastructure to technology giants such as HP, Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and Starlink.

Any reliance on these companies for the underlying technology that supports an electronic voting system carries geopolitical and economic risks, including potential external interference or undue influence over South Africa’s electoral processes.

By initiating this important dialogue through the Green Paper that set the foundation for the conference, the IEC has signalled its commitment to ensuring that any potential shift towards e-voting is guided by rigorous analysis, stakeholder engagement, and a clear understanding of the risks and safeguards required to protect the integrity of our democratic processes.

Let’s make our democracy work!

Khaas is founder and chairman of Public Interest SA, an IEC-accredited election observer. The organisation’s e-Government Barometer initiative serves as a vital tool for assessing and monitoring the state of e-government in South Africa, evaluating digital transformation efforts within public institutions. Furthermore, the organisation’s Electoral Integrity Project is committed to safeguarding and enhancing the credibility of South Africa’s electoral system.